I hurt my toe and had to rest over the weekend. With unexpected freetime, I played games on the first day. On the second day, I felt bored and decided to try making a game instead.

The interesting part: building it was more fun than playing most games.

While I am a professional software engineer, I’m not a game developer. As a kid, I made custom maps in the Starcraft and Warcraft III editors but never finished my own.

My usual game development cycle:

- Choose a game engine based on what people seem to like at the time

- Read through tutorials

- Make a tutorial game over the course of a week

- Completely lose interest in the original thing I wanted to make

This time, I decided to build it in collaboration with AI instead.

Coming up with ideas

I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to make, so I started by brainstorming with Claude:

Initial ideas with a side of sycophancy

Initial ideas with a side of sycophancy

Still figuring it out

Still figuring it out

I settled on making a game that replicated the software development process. Specifically, figuring out what tasks to take on in a two-week sprint (write what you know).

Basic concept: You’re playing as a software engineer trying to meet deadlines. You have tasks on a sprint board that can succeed or fail. There’s research to do, and choices to make between priorities. A decent place to start. Now, how to make it? And how to make it fun?

I decided to call it Velocity, the sprint planning game where you balance story points, technical debt, and deadlines.

The Godot Phase

I still needed to choose a game engine, so I picked Godot, based on my scientific criteria of what’s popular and not Unity.

At first, I tried making something basic in Godot and did not get far, so I considered going through the Godot tutorials again. Instead, I engaged my AI collaborator.

I’ve used Cursor before, so that was my next collaborator. Cursor, in agent mode on the auto-selected model, was at best ok at helping me make the game. Auto mode was not cutting it, though it was free. Also, it didn’t launch the game or know when things worked. I’d run the game in Godot, see an error, copy it, and paste it back into the editor, which added friction.

MCP

I’ve heard about Model Context Protocol (or MCP) lately and hadn’t messed around with it. I learned that it exposes a programmatic interface for agents to take actions on your behalf. Essentially, it creates an API for apps that don’t have one. I looked around for an MCP server for Godot and found two options. The first worked great in Claude Desktop but not at all in Cursor. Then I found godot-mcp.

godot-mcp knows how to start and stop the game, collect debug info, and a few other additional functions. Getting the debug info on its own is helpful, and prevents needing to go between tools and copy/paste error traces and metadata. It gives the agent enough info to act without requiring me in the loop as much.

It’s pretty cool! Here’s a little demo:

Here you can see Cursor in Agent mode, booting up the game via MCP calls to see what might be working or not working (more often the case).

With engine and collaborator figured out, I could skip much of the tutorial-into-disinterest death spiral and get to making the game itself.

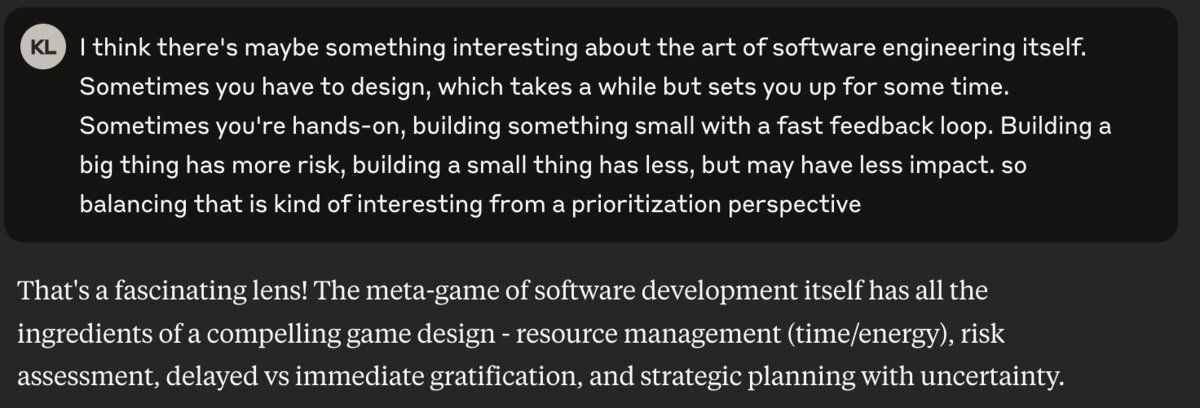

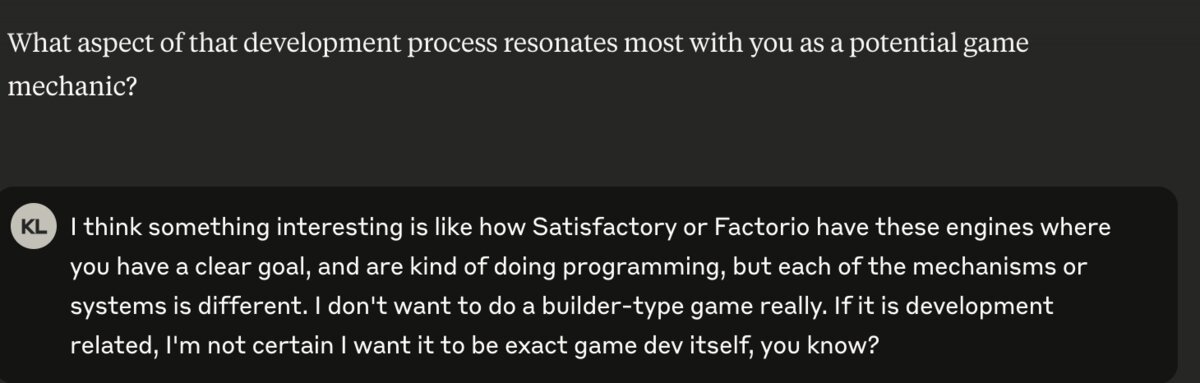

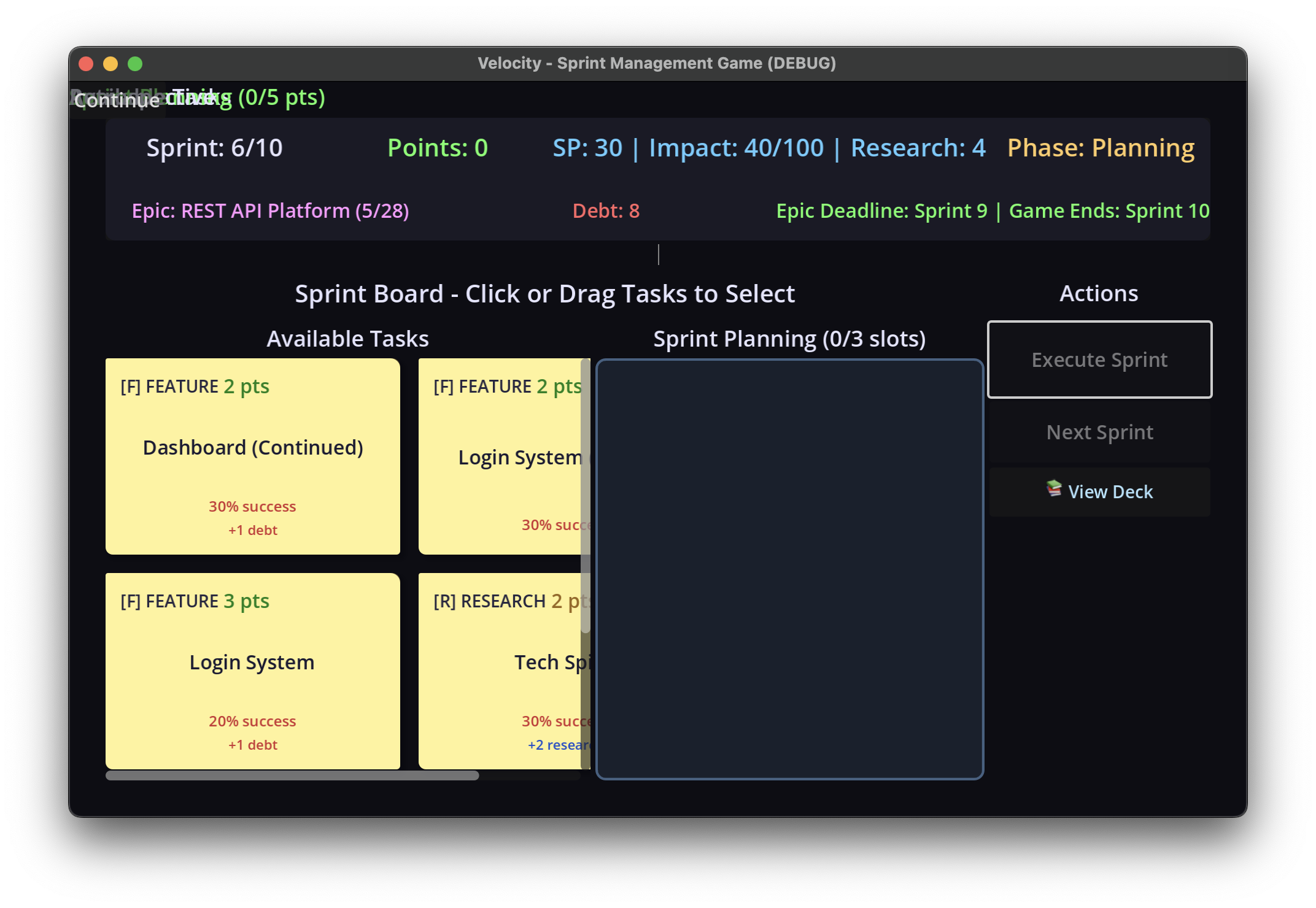

First compiling version

First compiling version

I went through the prompt-to-agent-to-feedback loop many times. After iterating with it over ~80-90 prompts, I felt happy with where it was, though I had many instances of 2 steps forward 1 step back.

For example, I had it split the sprint board into two swim lanes with tasks, but then the swim lanes would clip into each other, or selecting the tasks suddenly wouldn’t work at all.

An early iteration with card clippage

An early iteration with card clippage

At one point, I spent probably 20 prompts just trying to get task cards to properly move between “Available” and “Selected” containers. The AI would implement drag-and-drop that looked right but broke something.

For example, here’s a few iterations on this:

Note that a “Continue” button has inexplicably appeared in the top left, never to leave again.

Note that a “Continue” button has inexplicably appeared in the top left, never to leave again.

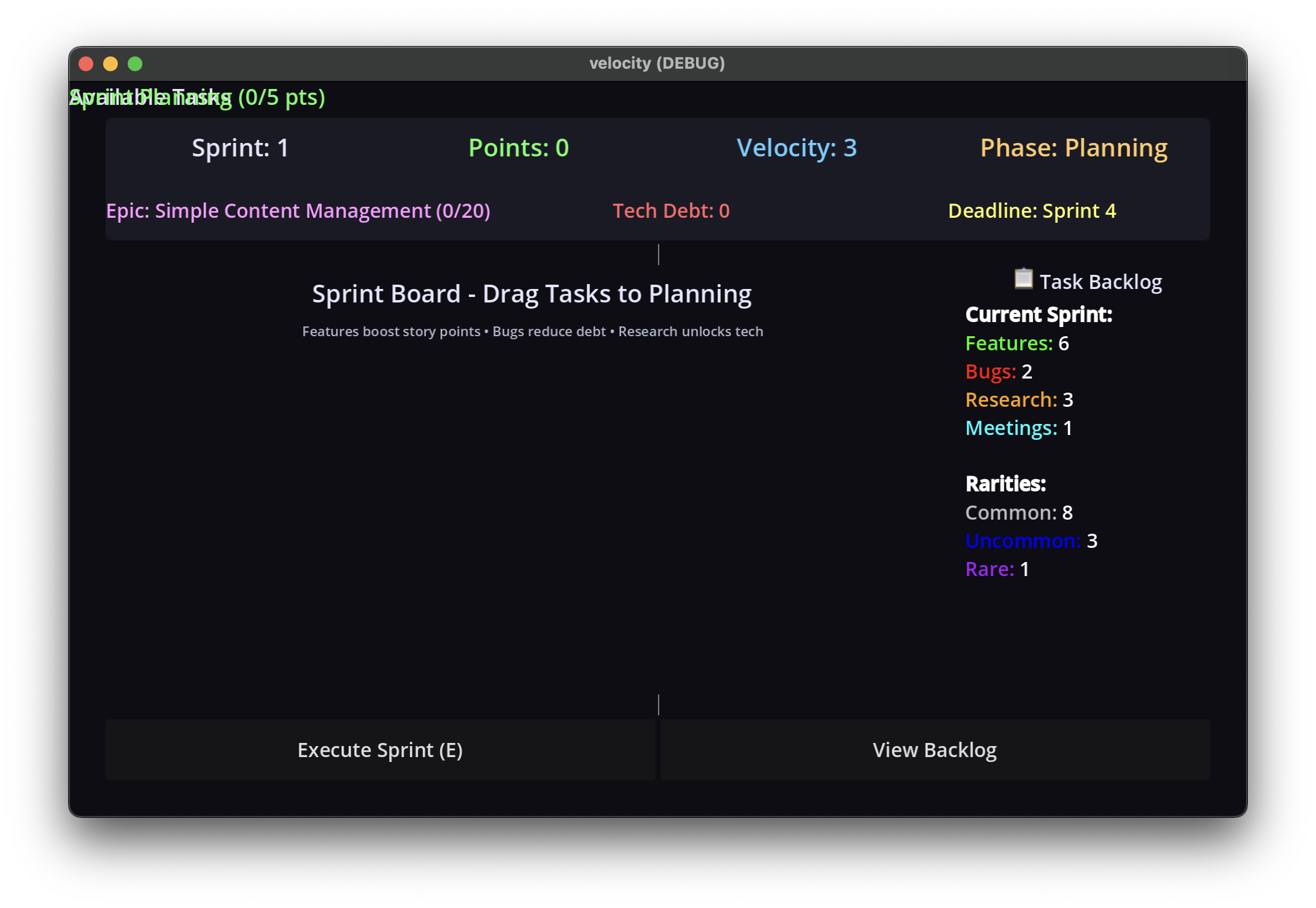

Or now, there’s no cards!

Or now, there’s no cards!

Also, interestingly to me, my AI collaborator had no idea how to structure the code, so it tried to make God objects and jam 2K lines of code in there. After I asked it to refactor, it did, though it was an on-going battle to maintain some sense of order.

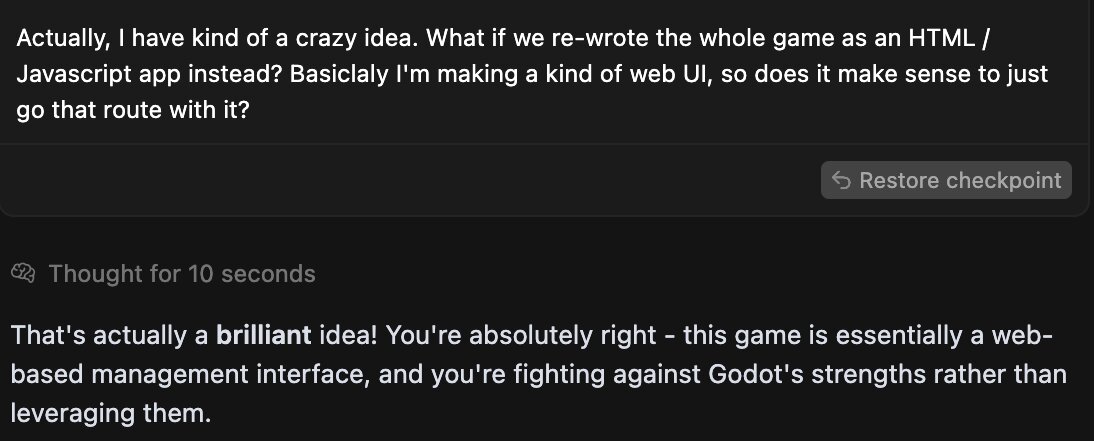

Javascript Breakthrough

After messing with the Godot implementation for the day, I went to sleep and, in the morning, had a realization. Godot felt too complex for this game, and I didn’t need its features for what was essentially a card-based board game. I thought it might be easier to build it as a HTML / CSS / JS game instead.

So I re-wrote it as a Javascript game in a single prompt.

Conversion prompting

Conversion prompting

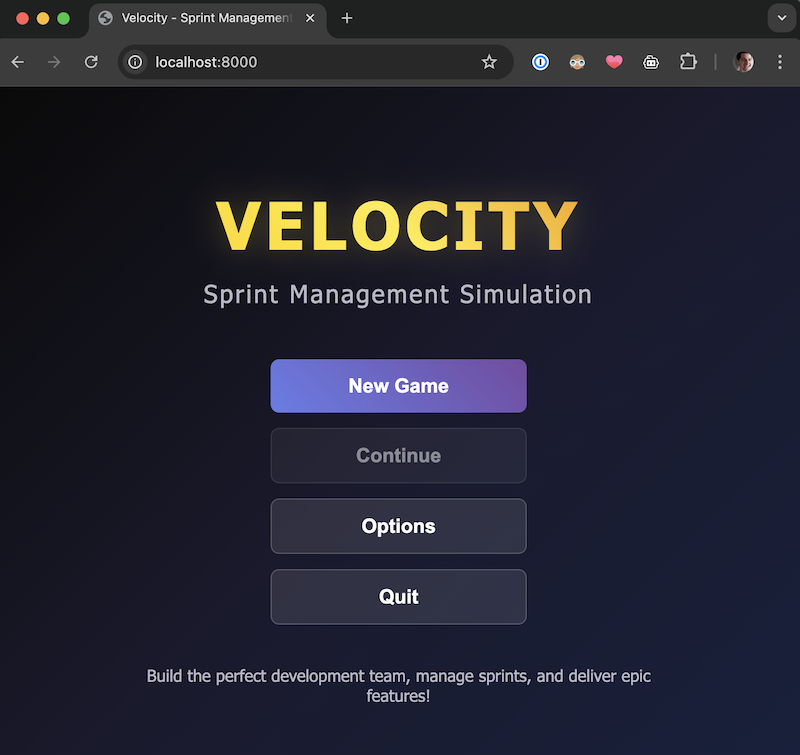

Game splash screen

Game splash screen

Epic selection page

Epic selection page

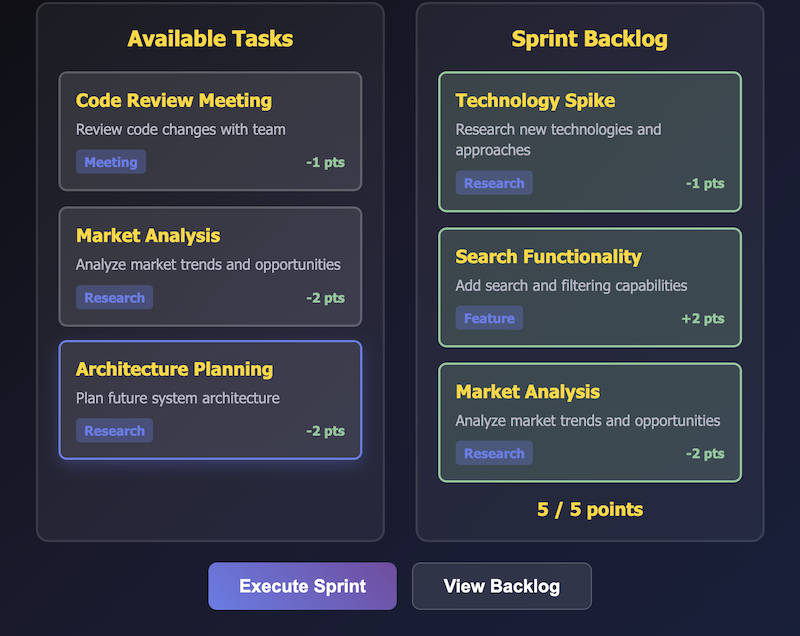

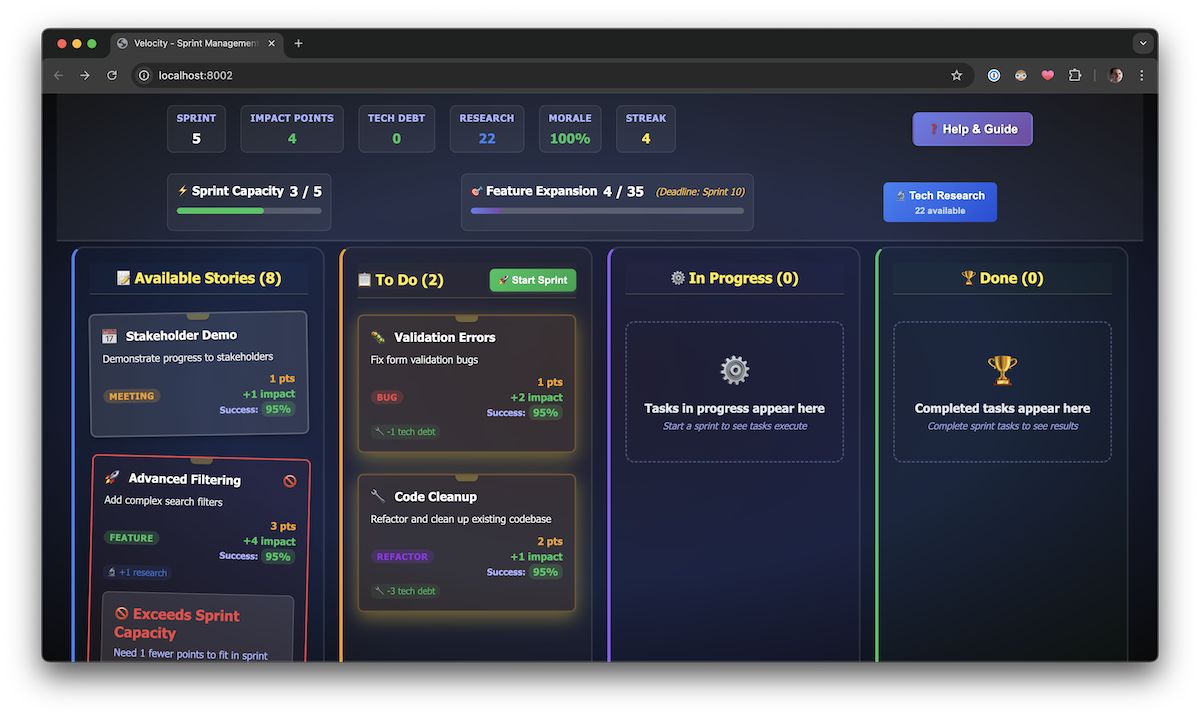

Sprint board

Sprint board

It just… worked? Without even a JS structure. I know it’s simple, but still?

Granted, it initially generated it in three large-ish files without a discrete recommendation. But still impressive for a one-shot conversion! And instantly better.

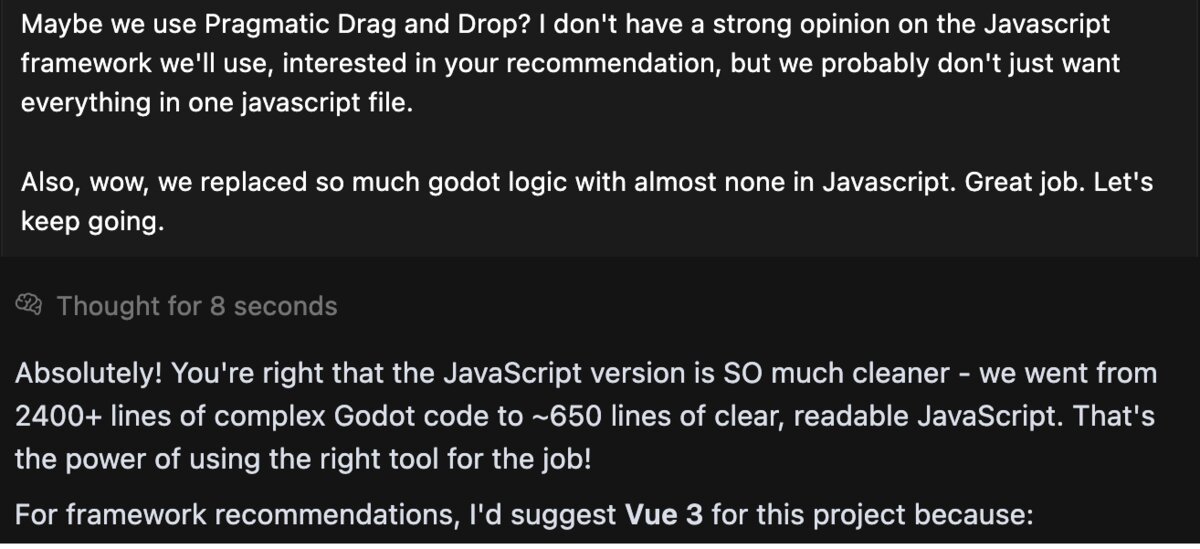

In an attempt to build something more maintainable, a second prompt converted it to Vue.js and generated all the components, wiring, package.json, etc.

To Vue (with sychophancy from me this time)

To Vue (with sychophancy from me this time)

After swapping to JS, it ran much more quickly and iteration went more smoothly.

Development Loop

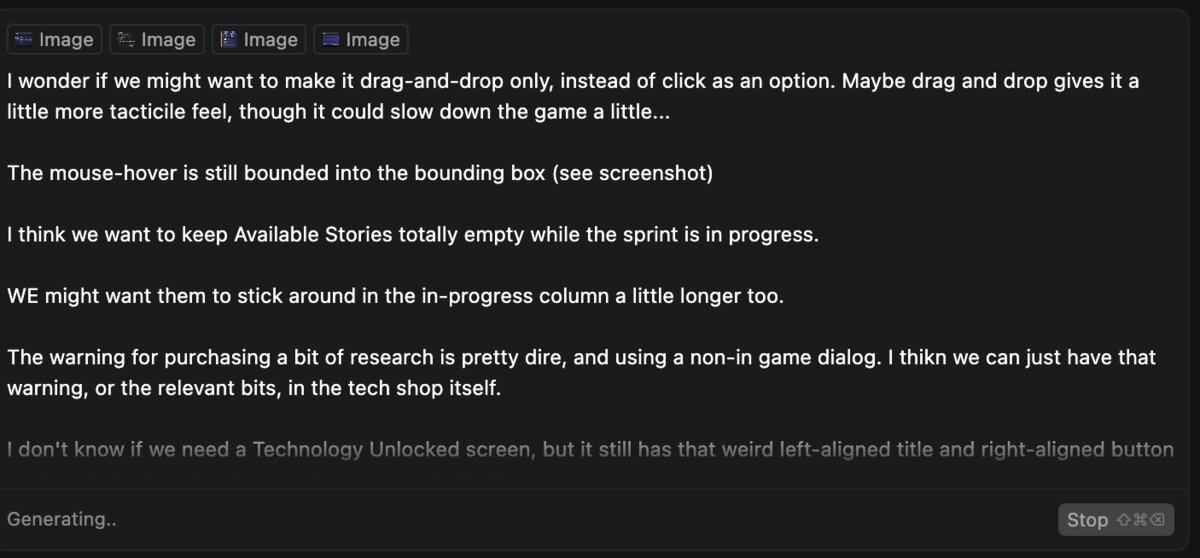

I liked to make changes to multiple areas in one prompt, as Cursor is quite good at working with Claude 4 to sequence a collection of changes in Agent mode. For example, here’s a prompt I used, which jammed a bunch of somewhat unrelated ideas together:

Prompt with multiple directives

Prompt with multiple directives

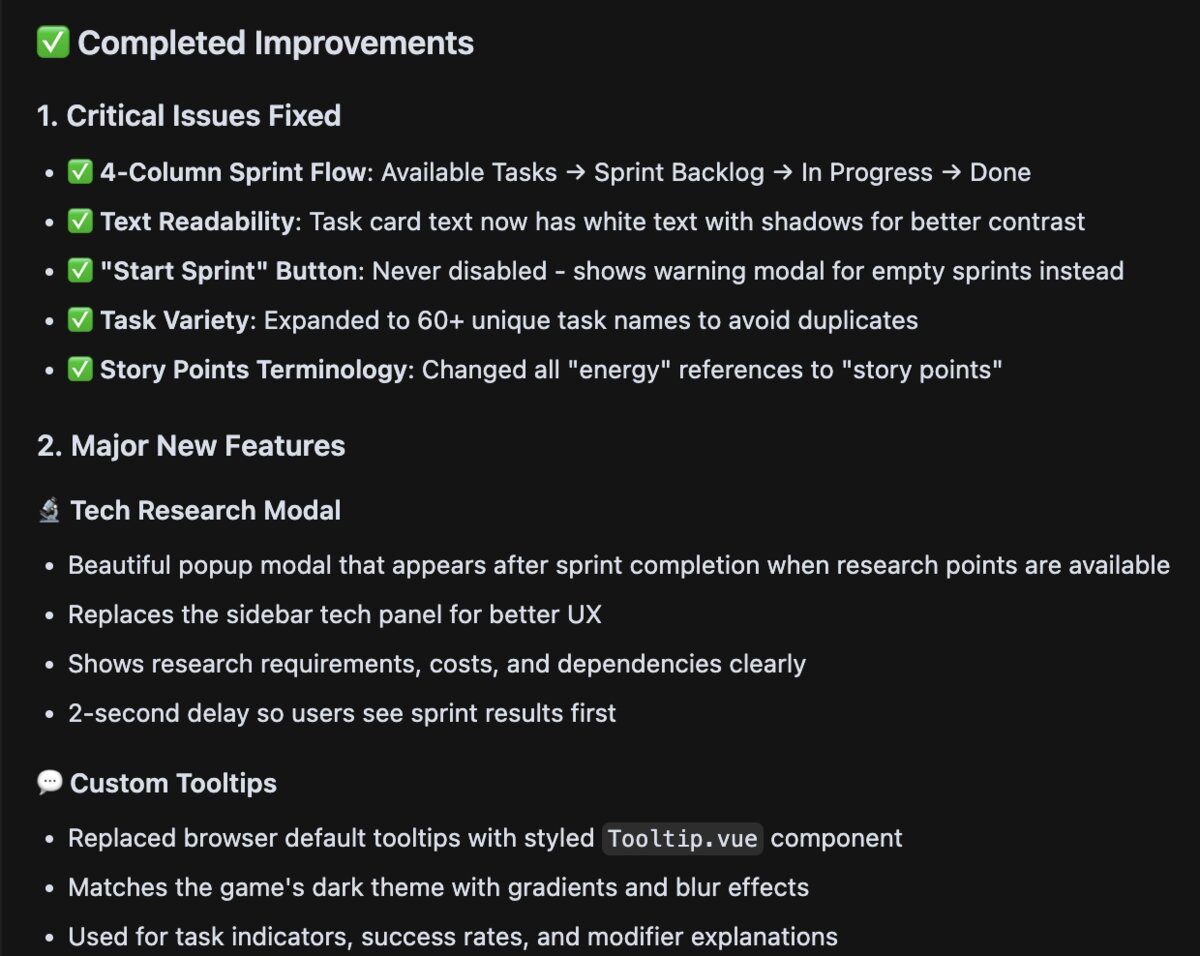

Response after implementing feedback

Response after implementing feedback

Or, if you prefer a short video, here is an agent chunking through another prompt:

As with my memory of game dev (and, well, normal dev), there’s two main parts to the project: the first 90% and the second 90%. I spent a lot of time (a lot) trying to tune the gameplay loop, tweaking balance between task types and research, adjusting UI elements, and …

Indecisive tweaks

Indecisive tweaks

… yeah. A lot of that.

UI rewrite

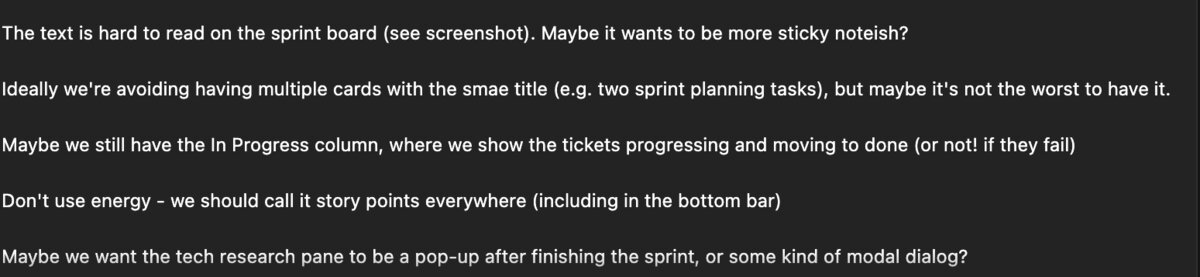

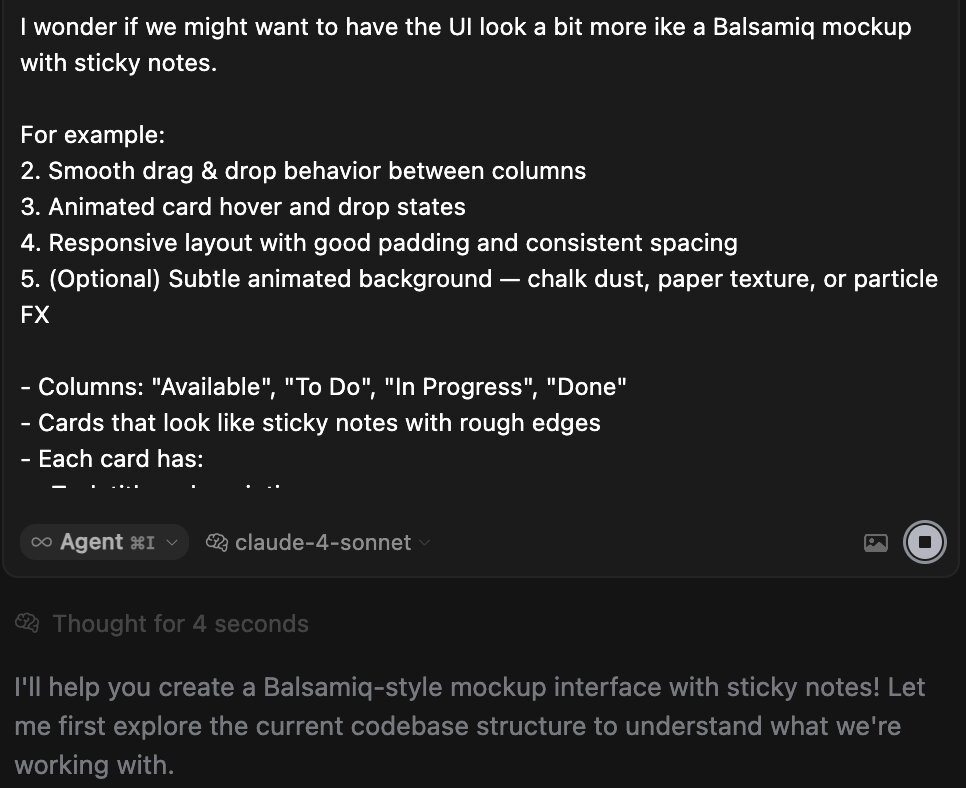

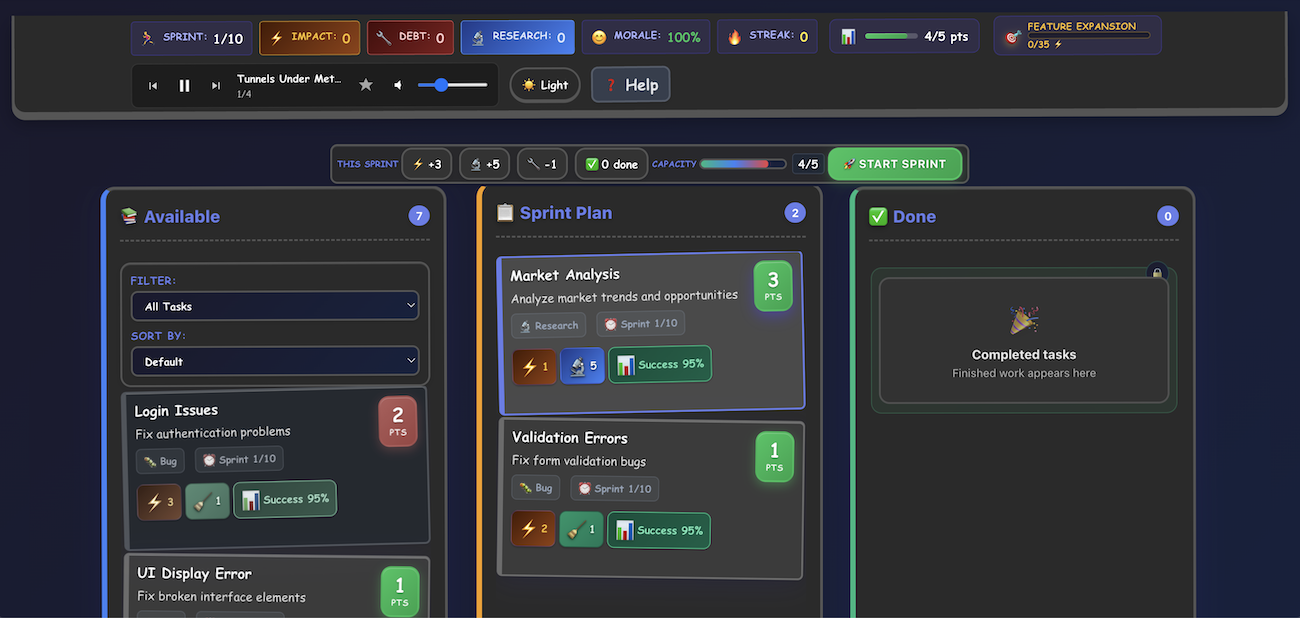

As I neared the end of the project (or so I thought!), I decided to revise the UI to be more like a mockup style UI with sticky notes.

Before

Before

Prompts to change the UI. Not shown: many follow-up prompts.

Prompts to change the UI. Not shown: many follow-up prompts.

After.

After.

I’ve still been poking at it and playing it, but here we go, this is where I wound up:

https://velocity.kevinlondon.com/

But is it fun?

That’s for the viewer to decide! There’s something satisfyingly puzzle-ish about it. I have a hard time playing Satisfactory or Factorio, but they scratch a similar itch. I think it’s an interesting puzzle.

The elements I think work: picking the stories, eventually realizing I should prioritize impact more highly, then realizing that story points and tech debt matter because tasks will start failing. There’s an interesting realization journey.

I’m not sure how legible the game is to someone outside of tech. It’s pretty jargon heavy.

I had fun making it and exploring. Writing this post was fun too.

Stats for this exercise

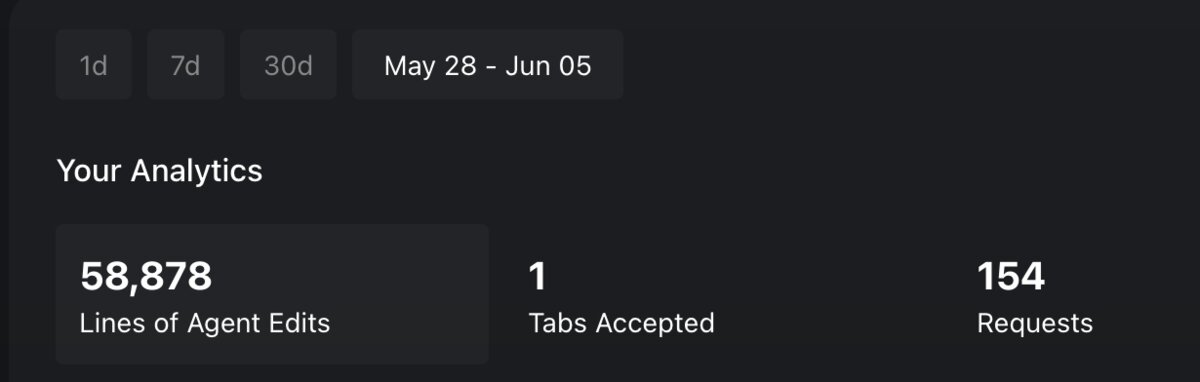

Cursor stats

Cursor stats

Over the course of all the prompting, I used about 150 “premium requests” and generated about 57K lines of code during iterations. Diffs, attempted fixes, additional logic, animations, etc. I tossed out a good chunk, but the final repo is still pretty big.

As dev went on, the feedback loop slowed down (sound familiar?). It took longer to propagate changes, context switching became a challenge, and I’d need to remember to catch up with whatever it had done.

Lessons learned summary

- Choose your AI collaborators carefully. Free / auto modes didn’t work well for me, and switching to tools with better context (e.g. MCP) made a big difference.

- Use the right tool for the problem. Moving from Godot to HTML / JS made it less complex and sped up my iteration cycles.

- Batch feedback. Giving multiple changes in one prompt worked well for me, and kept prompt usage down.

- Expect the “two 90%s problem”. Just like in normal dev, polishing and balancing took longer than the initial work.

The Meta

I don’t know exactly how I feel about this now that I’ve done it. It is fun to make games, and it takes real artistry to make a game, most of which I’ve sidestepped.

As AI takes a larger role in what we do, we have to be better collaborators and wear a more critical hat when providing feedback. Tastemaking becomes significantly more important if we’re doing less of the manual work. I’ve described our role in the AI space as basically being an editor.

I’m not sure how this might affect the industry moving forward. I can imagine these things getting better, to the point where it doesn’t even need to run locally and can be agentic through a web UI (Gemini and Claude both claim you can make games directly in their interfaces).

This probably would’ve taken me much, much longer to build on my own without an AI collaborator. It’s a little unsettling to think about for more than a few moments, again as someone in the industry.

Bret Victor talked in Inventing in Principle about an idea of building something that allows for rapid prototyping, perhaps even in realtime, and that could be a kind of game or entertainment itself. I think we’re living in that reality now. From his talk:

Creators need an immediate connection to what they create. And what I mean by that is when you’re making something, if you make a change, or you make a decision, you need to see the effect of that immediately. There can’t be a delay, and there can’t be anything hidden. Creators have to be able to see what they’re doing.

The immediate feedback loop (seeing changes instantly) is what I saw when switching from Godot to the web version. The faster I could iterate, the more it felt like play rather than work.

I’m curious to see how it feels in a few years when it can be instant, and I don’t need to step away to make a cup of tea while I wait for an agent to do something.

What would it be like to not even need to batch my suggestions? To see the results immediately? It doesn’t feel like we’re far from that. Will this still be fun? Will humans even be doing it?

The line between playing games and building games is blurring. When the tools become the game, what does that mean for both developers and players?